Implementing the Socio-economic

Duty

A review of evidence on socio-economic disadvantage

and inequalities of outcome

Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg.

This document is also available in Welsh.

© Crown Copyright Digital ISBN 978-1-80391-059-8

SOCIAL RESEARCH NUMBER:

68/2021

PUBLICATION DATE:

13/10/2021

Title: Implementing the Socio-economic Duty

Subtitle: A review of evidence on socio-economic disadvantage

and inequalities of outcome

Author(s): Chloe Mills

Full Research Report: Mills, C. (2021). Implementing the Socio-economic

Duty: A review of evidence on socio-economic disadvantage and inequalities

of outcome. Cardiff: Welsh Government, GSR report number 68/2021>

Available at: https://gov.wales/evidence-review-socio-economic-disadvantage-

and-inequalities-outcome

This report was produced as part of a three month Welsh Government PhD

internship organised through the ESRC Wales Doctoral Training Programme

(DTP) and Welsh Government. Views expressed in this report are those of the

researcher and not necessarily those of the Welsh Government. This

evidence review reflects the terminology included within the evidence and

therefore may not fully reflect the Social Model of Disability. Welsh

Government is fully committed to the Social Model of Disability

For further information please contact:

Steven Macey

Communities Division

Welsh Government

Cathays Park

Cardiff

CF10 3NQ

Email: [email protected]

1

Table of contents

List of tables ............................................................................................................... 1

List of figures .............................................................................................................. 1

Glossary ..................................................................................................................... 2

1. Introduction .................................................................................................... 3

2. Methodology ................................................................................................ 11

3. Education..................................................................................................... 13

4. Work ............................................................................................................ 18

5. Living standards .......................................................................................... 24

6. Health .......................................................................................................... 31

7. Justice ......................................................................................................... 42

8. Participation ................................................................................................. 47

9. Conclusions ................................................................................................. 52

References ............................................................................................................... 55

List of tables

Table 1.1 Links to further resources: General. ......................................................... 10

List of figures

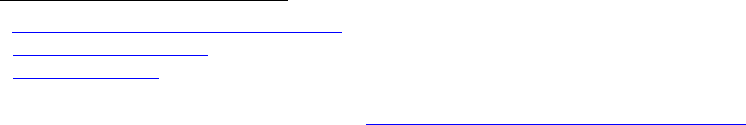

Figure 1.1: The links between socio-economic disadvantage and inequalities of

outcome. ........................................................................................................ 4

Figure 1.2: Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation. ........................................................ 6

Figure 3.1: Achievement based on free school meal eligibility. ................................ 14

Figure 3.2: Factors involved in the ‘attainment gap’. ................................................ 17

Figure 4.1: Factors implicated in the poverty premium ............................................. 19

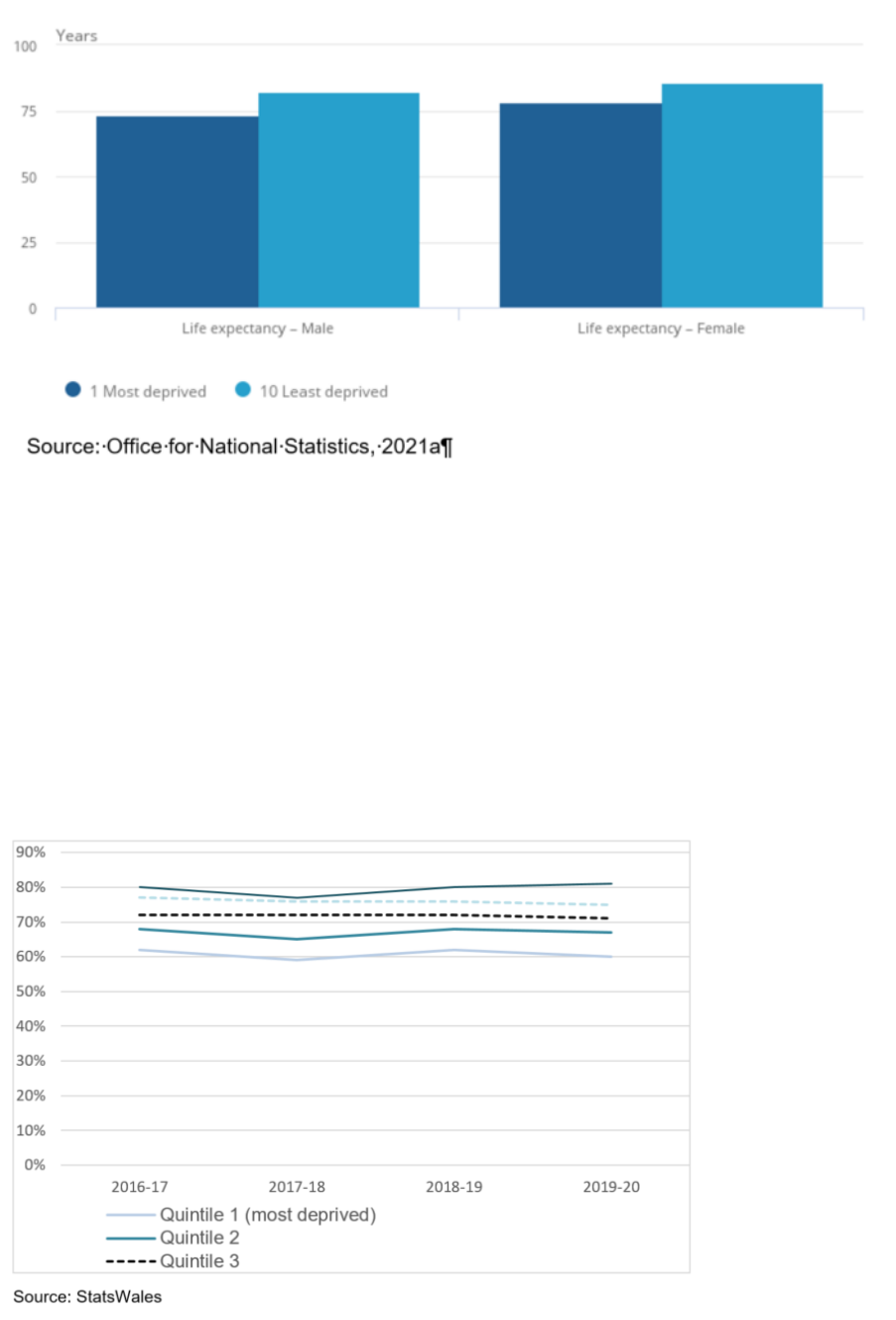

Figure 6.1: Life expectancy for males and females in the most deprived and least

deprived area of Wales ................................................................................ 33

Figure 6.2: Percentage of adults (aged 16+) reporting good or very good health by

WIMD deprivation quintile. ........................................................................... 33

Figure 6.3: Mental well-being by deprivation quintile in Wales. ................................ 35

Figure 6.4: Disabled status by area

deprivation…………………………………………40

2

Glossary

Acronym/Key word Definition

Intersectionality The interconnected nature of social categorisations such as

race, class, and gender which create overlapping and

interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage.

EHRC Equality and Human Rights Commission

FSM Free school meals

LGBTQ+ Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning/queer,

and others, where the plus represents all other sexual

identities and communities.

FGC Future Generations Commissioner for Wales

JRF Joseph Rowntree Foundation

ONS Office for National Statistics

SED Socio-economic Duty

BMI Body mass index

3

1. Introduction

1.1 The Socio-economic Duty (or just “the Duty”) came into force in Wales on

March 31

st

2021 and requires specified public bodies, when making strategic

decisions (such as deciding priorities and setting objectives), to consider

how their decisions might help reduce the inequalities associated with socio-

economic disadvantage. This means that now, when making decisions,

public bodies in Wales will have a legal responsibility to consider how their

decisions will improve outcomes for people experiencing socio-economic

disadvantage. The Duty will be key in supporting the most vulnerable people

in our society, especially as Wales recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic,

and for the longer term. As the guidance states:

“Commencing the Duty will not compete with or override other duties such

as the Equality Act, 2010 Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED), the

Children and Families (Wales) Measure 2010 and the Well-being Duty

under the Well-being of Future Generations Act 2015. It is our intention

that commencing the Duty will complement these duties by further

contributing towards Wales’ long term well-being goals, in particular “A

more equal Wales” and “A Wales of cohesive communities”.”

1.2 The Duty aligns with other pieces of Welsh Government legislation such as

the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015

1

and the Equality Act

2010

2

, as well as work such as the national strategy Prosperity for All

3

which

was in place during the development of the Duty

4

. The guidance directly links

to the Well-being of Future Generations Act and supports its common

purpose of delivering a public service that meets the needs of the present

without compromising the ability of future generations. In taking account of

evidence around socio-economic disadvantage it is therefore suggested in

the guidance that evidence around future trends is considered. Although

1

Well-being of Future Generations Act

2

The Equality Act 2010

3

Prosperity for All

4

This strategy was in place while the Duty was being developed and implemented, for details of the

current Programme for Government see: Programme for government | GOV.WALES

4

beyond the scope of this report to fully consider the linkages between future

trends and socio-economic disadvantage, trends in inequalities have been

highlighted where relevant. Other resources such as the Welsh

Government’s Future Trends Report

5

outline the key factors influencing our

social, cultural, economic and environmental futures and can be used to

support analysis around impacts on future generations for groups facing

socio-economic disadvantage.

Figure 1.1: The links between socio-economic disadvantage and inequalities of

outcome.

1.3 To achieve the overall aim of the Duty, which is to deliver better outcomes

for those who experience socio-economic disadvantage, it is important for

policymakers to be informed by up-to-date evidence on socio-economic

5

Future Trends Report

Source: Socioeconomic Duty Guidance

5

disadvantage and the key inequalities of outcome that arise from it. The

guidance states that public bodies must be able to provide evidence on how

they are meeting their statutory requirements under the Duty, including

taking account of evidence which identifies any likely impacts of decisions in

relation to the Socio-economic Duty and evidence of how due regard was

given in order to reduce inequalities of outcome as a result of socio-

economic disadvantage. This report aims to provide an overview of how

socio-economic disadvantage affects the people of Wales and how it leads

to inequalities of outcome in key areas, especially for particular groups at

increased risk of facing disadvantage.

1.4 For more guidance on the Duty itself, please see the Further Reading

section at the end of this chapter.

Socio-economic disadvantage in Wales

1.5 Across Wales, 710,000 people live in poverty and 23 per cent of the nation

live in relative income poverty (Welsh Government, 2021g). Overall poverty

rates have remained steady over the last five years in Wales, and while child

poverty has been falling, pensioner poverty has been rising (Welsh

Government, 2019f). A total of 16 per cent of non-pensioner adults in Wales

were classed as materially deprived in 2019/20, which means that they were

unable to afford things such as keeping the house warm enough (Welsh

Government, 2021e). When asked how comfortably they were keeping up

with bills, 68 per cent of working-age adults were keeping up without any

difficulties and the rest stated that it was a struggle from time to time (23 per

cent) or it was a constant struggle (6 per cent). Figure 1.2 shows the most

and least deprived areas across Wales according to the latest Welsh Index

of Multiple Deprivation. The most deprived areas are concentrated in the

south Wales cities and valleys and in some north Wales coastal and border

towns. These areas also tend to be the most densely populated areas of

Wales.

6

Figure 1.2: Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation.

1.6 Disadvantageous socio-economic circumstances have long-lasting impacts

on all areas of someone’s life, from birth through to adulthood. This is

because differences in wealth or opportunity, i.e., socio-economic

deprivation, restrict people’s opportunities and options in life. Thus, poverty

is linked to poorer educational and work or health-related outcomes.

Specifically, socio-economic disadvantage can result in long-term

inequalities of outcome, such as the following which are described in the

Socio-economic Duty:

Poorer health and mental health;

Lower healthy life expectancy;

Poorer skills and educational attainment;

Lower paid work;

Greater chance of being a victim of crime and not feeling safe;

Poorer participation in public life;

Greater chance of living in less than adequate housing; and

Poorer access to transport and public services.

1.7 These inequalities of outcomes are why addressing socio-economic

disadvantage is so important. The Duty is aimed at reducing inequalities

through requiring specified public bodies to give due regard to the need to

Source: Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation

7

reduce inequalities that exist as a result of socio-economic disadvantage,

when taking strategic decisions. Socio-economic disadvantage

disproportionately affects certain groups, including women, lone parents,

racial and ethnic minorities, children, disabled people, and those living in

rural areas (Alston, 2018).

1.8 The COVID-19 pandemic has also exacerbated some of the disadvantages

already faced by people in Wales, as it has affected certain groups much

more than others (Welsh Government, 2020a); the impacts of the pandemic

are mentioned throughout this report. Guidance for the Duty suggests that

public bodies consider how their decisions might be further impacted when

considering communities and places of impact as well as protected

characteristics. This report considers the further impact of intersectionality in

relation to inequalities of outcome experienced.

The key aims of this literature review

1.9 The aim of this report is to provide a source of evidence that can be used

when decision makers are implementing the Duty. This document will

summarise the inequalities of outcome that arise from socio-economic

disadvantage, particularly highlighting the impacts on people with protected

characteristics as well as communities and places of interest. It will review

existing evidence of the impacts of socio-economic deprivation in six key

areas based on the ‘Is Wales Fairer?’ Report (EHRC, 2018): education,

work, health, living standards, justice, and participation. The research

objectives and methodological approach are outlined in Section 2.

1.10

It is designed to be a quick reference guide providing a general overview of

the evidence in different areas related to socio-economic disadvantage. It

does not go into extensive detail on every topic, but it does signpost to

additional information in each area which can be consulted. The report is not

prescriptive and does not provide instructions for implementing the Duty, but

instead aims to provide information that policymakers can consider when

taking strategic decisions. This is a summary of evidence to consider when

giving due regard to consider those who are socio-economically

8

disadvantaged. It does not replace consulting people with lived experiences.

It is vital to gather opinions from the people impacted by policies, as,

ultimately, they are the true experts.

Definitions

1.11 Socio-economic disadvantage is defined in this review as it is defined in

the Duty: ‘living in less favourable social and economic circumstances than

others in the same society’. Experiencing socio-economic disadvantage may

include some or all of the following:

living in a deprived area;

having little or no savings;

having little or no income; and/or

experiencing material deprivation (that is, lacking the things which most

people would say are needed for an acceptable standard of living – such

as the ability to replace worn-out furniture or to afford adequate heating).

The first element listed in the definition above, “living in a deprived area”

(commonly identified in Wales through the use of the Welsh Index of

Multiple Deprivation), is different to the other elements which relate to the

circumstances of individuals or households. Not all those living in deprived

areas are necessarily deprived themselves in terms of individual metrics

on income, education or health etc (although many will be). However, they

may still experience socio-economic disadvantage as a result of living in a

deprived area. As seen in this report, evidence on inequality of outcomes

is often presented using area deprivation. This approach also has some

advantages over the individual approach in terms of stability, given the

way individuals can move in and out of deprivation in the short-term.

1.12 This definition of socio-economic disadvantage overlaps with the idea of

poverty. Poverty is a complex, multidimensional construct that has had

various definitions over time. In the UK, a common definition of poverty is

earning 60 per cent of the median UK household income. More recently, the

Social Metrics Commission (2020) has published reports summarising a new

9

measure of poverty that takes into account, among other factors, all material

resources, housing and childcare costs, and costs that arise from an

impairment. This report refers to some sources that have investigated

poverty explicitly, rather than socio-economic disadvantage, and when

referring to these sources the word poverty may be used as an

interchangeable term for socio-economic disadvantage.

1.13 The Scottish Government has already implemented its Socio-economic Duty

(the Fairer Scotland Duty), and a consultation report

6

discusses the

complexity that surrounds defining socio-economic disadvantage in depth.

1.14 Strategic decisions are those which affect how the relevant public body

fulfils its intended statutory purpose over a significant period of time.

Inequality of outcome relates to any measurable differences in outcome

between those who have experienced socio-economic disadvantage and the

rest of the population. Relevant public bodies include Welsh Ministers,

Local Authorities, Health Boards, NHS Trusts, Fire and Rescue, National

Parks, Welsh Revenue Authorities, and Special Health Authorities.

1.15 It is important to highlight the intersectionality that exists when examining

socio-economic disadvantage and inequalities of outcome. Intersectionality

is the connected nature of social categories such as race, class, or gender

that create overlapping systems of disadvantage. For example, socio-

economic disadvantage is often compounded by other factors that can lead

to inequalities of outcome, such as race or gender. This review explores the

greater impact that socio-economic disadvantage can have on particular

communities in Wales, highlighting the intersectionality in inequalities of

outcomes facing vulnerable groups. Communities of interest are those

who share an identity e.g. lone parents, carers; those who share one or

more protected characteristic e.g. LGBTQ+, older people; groups of people

who have shared an experience e.g. homelessness, the same local

health/social care system or local service. Communities of place are those

who share a geographical location (e.g. people living in rural areas).

6

Consultation on the socio-economic duty: analysis of responses (Scottish Government)

10

Protected characteristics are defined in the Equality Act (2010) as age,

disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy

and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation. Relevant

public bodies are to eliminate all forms of discrimination, advance equality of

opportunity and promote good relations between people sharing protected

characteristics and those who do not share a protected characteristic.

1.16 The structure of this report is as follows. Section 2 outlines the methodology

and limitations of this work. Sections 3 to 8 summarise the evidence in the

areas of education, work, living standards, health, justice, and participation,

respectively. Each of these sections is concluded by a list of key sources for

further reading. The report finishes with a conclusion of the main points

outlined in this document.

1.17 Table 1.1 includes links to key policy documents for further background

reading.

Table 1.1: Links to further resources: General.

Socio-economic Duty: Overview and FAQ

Socio-economic Duty: Guidance

Socio-economic Duty: Scrutiny framework

A More Equal Wales: the Socio-Economic Duty. Examples of inequalities of outcome

due to socio-economic disadvantage and COVID-19

Measurement framework for equality and human rights (Equality and Human Rights

Commission)

Is Wales Fairer? (2018) (Equality and Human Rights Commission)

Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015

Well-being of Wales: 2021 Report

Future Generations

The Future Generations Report 2020

11

2. Methodology

2.1 This report presents a rapid literature review on the key inequalities of

outcome due to socio-economic disadvantage in six key areas. These areas

are based on the Equality and Human Rights Commission’s Equality and

Human Rights Measurement Framework and are: education, work, health,

living standards, justice, and participation.

2.2 This review considers various sources of information to explore the short-

and long-term effects that socio-economic disadvantage has on people,

primarily the people of Wales, using both academic and government

research literature. This report examines evidence across the UK but draws

primarily on Welsh sources.

2.3 Desk-based evidence from several key sources was drawn upon, including

reports by the Welsh Government and the Equality and Human Rights

Commission, academic literature, and work by non-partisan organisations

such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Due to time constraints, a rapid

literature review was undertaken rather than a systematic or rapid evidence

assessment, and thus specific inclusion/exclusion criteria and appraisal

methods are not specified. In general, evidence was identified for inclusion

through consultation with social research leads in the Welsh Government

and online keyword searches. Key websites consulted were the Welsh

Government website, StatsWales, and Google Scholar. Searches were

conducted by searching for relevant terms, e.g. education AND deprivation

OR inequality OR outcomes OR disadvantage AND UK or Britain or Wales.

Key sources consulted are listed at the end of each section.

2.4 To support the researchers understanding of the policy context, and to

ensure a continuing dialogue between the research and the work of the

Welsh Government Socio-economic Duty policy team, emerging findings

presentations were held regularly to manage the scope of the project. The

benefits of a literature review in this style is that it can be carried out by one

12

person in a short amount of time

7

.Thus, the scope was narrowed and the

research objectives were defined as follows:

To present a picture of socio-economic disadvantage and the related

inequalities of outcome in Wales and;

To summarise research on socio-economic disadvantage and related

inequalities of outcome for particular communities, focusing on those with

protected characteristics and communities and/or places of interest.

2.5 Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all research activities, consultations with

policy leads, and presentations were held remotely.

Limitations of the Method

2.6 Due to time constraints, the secondary evidence reviewed during this study

was appraised using literature review rather than systematic review

techniques. Literature reviews are less robust in generating an evidence

base than systematic reviews as they are prone to selection and publication

bias and do not use as robust methodologies as systematic reviews, meta

analyses, or rapid evidence assessments. They do not define the

exclusion/inclusion criteria or have to specify the appraisal methods or how

conclusions have been reached. For these reasons, the literature review

supporting this research should be considered to give an indication of the

extent and nature of the evidence base, rather than an exhaustive summary

of the research landscape. While care was taken to evaluate the usefulness

and robustness of all sources, the findings should be interpreted with

caution.

7

See The Magenta Book (2020).

13

3. Education

Key inequalities of outcome due to socio-economic disadvantage –

Education.

Socio-economic deprivation is linked to worse educational outcomes (called

the ‘attainment gap’);

Students from lower socio-economic backgrounds are less likely to attend

university and;

Entry rates of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic people into higher education

are increasing and are proportionately higher than White students.

Background

3.1 Approximately 4 million children in the UK live in poverty (JRF, 2020) and, as

of 2019, a total of 29 per cent of children in Wales are in poverty which is

one of the highest rates in the UK (Bevan Foundation, 2019). The Bevan

Foundation (2019) reports a mixed message in regards to child poverty

indicator changes over time, with a slight recent reduction in the child

poverty rate overall but an increase in children living in poverty in larger

families and workless households.

3.2 Growing up in an environment of economic deprivation can have negative

impacts on children’s mental, social, emotional and behavioural

development, as well as their health and educational outcomes (Treanor,

2012). In fact, child poverty and unequal educational opportunities have

been linked, as children who experience disadvantages growing up (e.g.

children in poorer families, who live in more deprived areas, or live in

inadequate housing) are less likely to gain qualifications in school and have

worse educational performance and prospects (JRF, 2007; Hirsch, 2007).

This difference in educational outcomes between socio-economically

disadvantaged children and others is often referred to as the ‘poverty gap’,

‘attainment gap’, or simply ‘the gap’.

14

The attainment gap

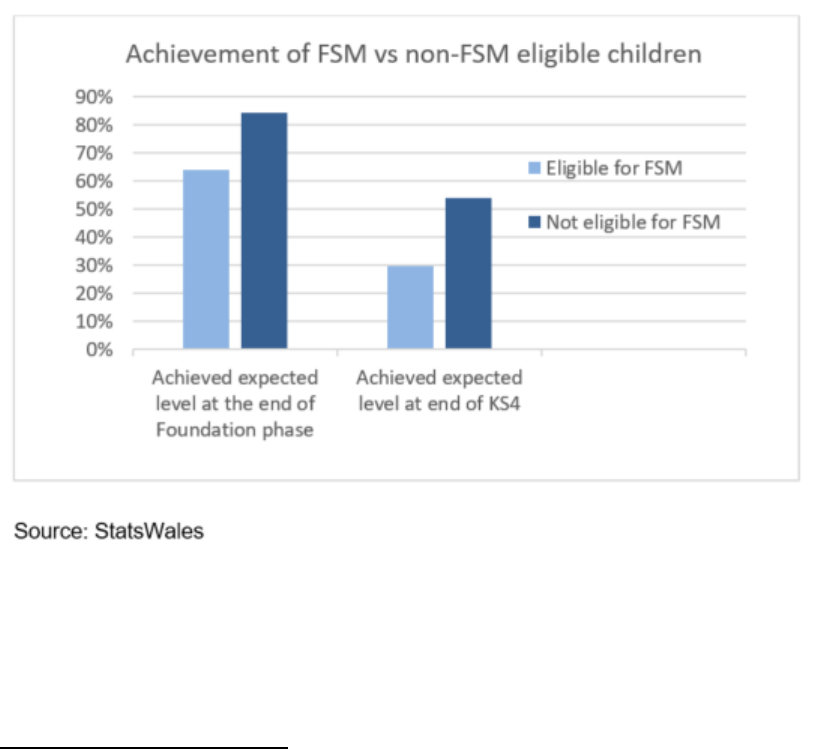

3.3 Eligibility for free school meals (FSM) is often used as a proxy indicator for

poverty and has been linked to poorer educational attainment (Welsh

Government, 2019a). In Wales, in 2019 a total of 63.8 per cent of children

eligible for FSM achieved the expected level at the end of the Foundation

Phase

8

compared to 84.2 per cent of children not eligible for FSM

(StatsWales, 2019). For older children, 29.5 per cent of those eligible for

FSM achieved the Level 2 threshold at Key Stage 4

9

, compared to 53.8 per

cent of children not eligible for FSM (Welsh Government, 2019c). GCSE

results also show worse grades for students eligible for FSM compared to

those who are not eligible (Welsh Government, 2020h).

Figure 3.1: Achievement based on free school meal eligibility (2019)

8

The Foundation Phase is the statutory curriculum for all 3 to 7 year olds in Wales

9

The Level 2 threshold at Key Stage 4 is a volume of qualifications at Level 2 equivalent to the volume

of five GSCEs at grade A*-C

15

3.4 In addition to different outcomes for school qualifications, children eligible for

FSM in Year 11 have decreased chances of achieving sustained

employment and increased likelihood of receiving out-of-work benefits as

adults (Department for Education, 2018).

3.5 Research conducted using the Millennium Cohort Study has found that the

attainment gap is apparent as early as 5-years-old in the areas of vocabulary

and school readiness, and is only compounded throughout the school years.

Furthermore, the chance of having affected development is higher if a child

has a lone parent, parent(s) with lower amounts of education, or if they come

from a Black, Asian or Minority Ethnic background (Hansen & Joshi, 2007).

3.6 Furthermore, the proportion of students from lower socio-economic

backgrounds attending university, especially universities in the top of the

league tables, has historically been disproportionally low, with those from the

highest socio-economic backgrounds more likely to attend university

(Department for Business Innovation and Skills, 2015). This gap in higher

education attendance may lead to an inequality of future outcomes, as

university graduates on the whole tend to go on to work in higher-paying

occupations. However, the gap in higher education participation between

students from higher and lower socio-economic backgrounds has been

narrowing over time and increased tuition fees introduced in 2012 do not

seem to be deterring enrolment (Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2012). Tuition

fees are devolved and so fee increases have not affected Wales to as great

an extent, as fees are reduced for Welsh-domiciled students.

Intersectionality

3.7 Girls generally achieve better exam results than boys, and Black, Asian and

Minority Ethnic groups also score better than white students, according to

the most recent examination results bulletin (Welsh Government, 2020h).

Data from the Universities and Colleges Admission Services (2021) show

that Minority Ethnic learners are attending university in higher numbers over

time and White pupils have had the lowest entry rates, proportionately, from

2006 to 2020.

16

3.8 There are compounding factors involved in economic deprivation and

educational outcomes. Being eligible for free school meals is the most

appropriate proxy indicator available for statistical analysis to investigate

how poverty affects school results, but other factors are at play too. For

example, grouping schools by disadvantage also shows an attainment gap

for pupils not eligible for FSM, showing that school-level deprivation (on the

larger geographic scale, rather than an individual’s circumstances) also has

an effect on future outcomes (Department for Education, 2018).

3.9 Housing, health inequalities, and labour market disadvantages (discussed in

the below section on Work) exacerbate the disadvantages already present

due to coming from a poorer background (Hirsch, 2007). For example, an

inadequate environment in which to do homework can make it harder to

engage with the educational process (JRF, 2020). Ethnicity also plays a role,

and some schemes, such as the Childcare Offer in Wales, may not always

reach all disadvantaged children due to things such as cultural barriers in the

case of some Minority Ethnic groups (Craig et al., 2007; Hughes & Jones,

2021).

3.10 These factors emphasise the cyclical and intersectional nature of poverty

and highlight the importance of breaking the poverty cycle as soon as

possible, before disadvantaged children experience further disadvantages as

adults and become unable to provide a good start in life for their own

children. Research has shown that wealthier parents tend to have wealthier

children, and that the main driver for this is the difference that children

receive in investments in their childhood education (Ayyar et al., 2021). This

intergenerational transmission of these inequalities is highlighted in the

Welsh Government’s Annual Equality Reports

10

and their Strategic Equality

Plans

11

. Figure 3.2 draws on this evidence on the cyclical and intersectional

nature of poverty, highlighting the links and connections between different

factors that are involved in the ‘attainment gap’ and showing that differences

in achievement can arise not just from economic factors (e.g. deprivation)

10

Welsh Government Annual Equality Reports

11

Welsh Government equality plan and objectives

17

but also other social factors too (living standards, race, or adverse childhood

experiences). The connections between these factors exemplify the poverty

‘web’ and cyclical nature of socio-economic deprivation.

Figure 3.2 Factors involved in the ‘attainment gap’.

Further reading on education and socio-economic disadvantage

Chicken and egg: child poverty and educational inequalities

Education attainment: Responding to the Coronavirus pandemic

Entry rates into higher education

Evaluation of the Childcare Offer: Year 3

Examination results in schools in Wales, 2019/20

JRF: Education in Wales

National Evaluation of Flying Start

Parent beliefs, behaviours and barriers: childcare and early education

Review of Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) policy: Report

18

4. Work

Key inequalities of outcome due to socio-economic disadvantage –

Work

Race, disability and gender pay disparities are still present in Wales;

Women are more likely to work part-time and earn less than men;

Lower-paid work is more likely to be stressful or hazardous;

Lower income means more struggle to afford basic necessities and;

Diversity, including neurodiversity, needs to be celebrated and barriers to

entering the workforce must be addressed.

Background and the Welsh context

4.1 Working does not preclude experiencing poverty. In the UK, in-work poverty

has risen over the last 5 years and a total of 12.7 per cent of workers live in

poverty due to low pay or limited hours (JRF, 2020). Working households

represent 56 per cent of people living in poverty in Wales, compared to 39

per cent measured 20 years ago (JRF, 2020). Most children living in poverty

live in working households at a rate of around seven in ten (Welsh

Government, 2019d) and families with children are most at risk of in-work

poverty, especially lone parents.

4.2 Low-paid work is the biggest contributor to in-work poverty as it makes it

very difficult to escape poverty when you are not paid enough or there are

not many well-paying jobs in your area (JRF, 2020). In Wales, 26 per cent of

employees earned less than the Real Living Wage in 2017/18 (JRF, 2020).

The Real Living Wage is a voluntary wage that is, according to the

organisation, closer to what people need for day-to-day costs. It currently

stands at £9.50 per hour compared to the UK National Living Wage which is

£8.91 per hour for workers over 23 years old. Salary levels in Wales were

found to be slightly lower than the UK as a whole. Median gross weekly

earnings for full-time adults working in Wales were £537.80 in April 2020,

19

compared to the UK average which was £585.50

12

(Welsh Government,

2020d). Statistics from May 2021 related to work in Wales show the

unemployment rate was 4.4 per cent, close to the UK average (Welsh

Government, 2021d).

4.3 Some sectors are particularly prone to contributing to in-work poverty such

as accommodation (e.g. hotels), catering, retail, and residential care, which

also tend to employ higher proportions of women (EHRC, 2018). Section 4.7

discusses the gender pay gap in more detail.

4.4 Being in economic deprivation while employed means that despite being

employed, you still may not have the required amount of money to meet

basic needs or deal with unexpected emergencies. Another aspect to

consider is that often the poorest households end up paying the most for

basic goods and services such as public transport and household bills – this

is known as the ‘poverty premium’ (Heykoop, 2018). For example, this can

result from using pre-payment meters for fuel or not switching to the

cheapest fuel tariff (due to perhaps not knowing how to or that you should or

risk aversion), or accessing high-cost credit. There are many factors that go

into the poverty premium and research has suggested that the cost of the

poverty premium may be around £490 per year per household. Table 4 lists

some of these contributing factors (Davies et al., 2016).

Figure 4.1: Factors implicated in the poverty premium.

12

This figure includes weighting to account for higher salaries in London and the South East compared

to the UK as a whole.

13

Note: Factors are listed in ascending order based on how much they cost people

Factors implicated in the poverty premium

13

Not switched to the cheapest fuel tariff

Factors related to where people live

Using higher-cost credit

Using pre-payment meters

Not paying by cheapest billing method

Insuring specific items

Paying to receive paper bills

Paying to access money

Source: Davies et al, 2016

20

4.5 Working part time or with insecure hours, or working in the ‘gig economy’

(e.g. food delivery, courier or working for a ride hailing service), means that

someone may work at times that are not conducive to arranging adequate

childcare. On the other hand, having children can restrict your flexibility and

the hours you want to work. Despite perhaps desiring more hours, workers

may be unable to get them; in fact, 18 per cent of low-paid workers say they

would like to work more hours, compared to 8 per cent of all workers who

are not low paid (JRF, 2020). Insecure employment, such as temporary,

agency or self-employed work, constituted 10 per cent of all employment in

2016/17 and those in insecure employment may not receive the same key

rights and protections at work and may experience impacts on their pay

(EHRC, 2018).

Intersectionality

4.6 Pay gaps and in-work poverty affect certain groups much more than others.

The risk of in-work poverty is greater for disabled and Minority Ethnic

workers. Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic workers are more likely to be in

relative income poverty and households including someone who is disabled

are more likely to struggle financially (EHRC, 2018). Furthermore, disabled

people are less likely to work in high-pay occupations, compared to non-

disabled people, and disabled people are twice as likely to be unemployed

as those without an impairment (EHRC, 2018). The Well-being of Wales

2020 report shows that pay gaps exist for women, disabled people, and

Minority Ethnic in Wales. The pay gaps for these groups are the smallest on

record, as, for example, the pay gap for women in full-time work which has

been closing through rising educational attainment and occupational

diversity (Connolly & Gregory, 2008). Wales has a smaller gender pay gap

(4.3 per cent) than the UK average (7.3 per cent), measured on a median

hourly full-time basis (Welsh Government, 2020d). However, gaps still

persist in several areas and the reasons behind them are complex.

21

4.7 The employment participation of women has been extensively analysed and

the research suggests that cultural expectations around having children and

providing childcare have a negative impact on the wages and careers of

women, contributing to the gender pay gap (Boeckmann et al., 2014).

Women are also more likely to work part-time (often to balance caring

responsibilities) or in low-pay occupations (EHRC, 2018), where there are

fewer opportunities for training and development. In fact, part-time work is

directly linked to decreased future earnings for women (Connolly & Gregory,

2008), which again contributes to the gender pay gap. Cultural expectations

can lead to further inequalities of outcome for ethnic minorities (Dale et al.,

2008). For example, some cultures, such as South East Asian cultures, may

place a greater emphasis on parenthood, leading to increased childcare

responsibilities for women that limit them taking part in certain aspects of

employment such as travelling far from home (Ibid). This restriction on

participation in the labour market for women in some cultures is a key

inequality of outcome that furthers the ethnicity and gender pay gaps in

Britain.

4.8 Women may also have negative or possibly discriminatory experiences

during pregnancy, maternity leave or on their return from maternity leave.

Research commissioned by The Department for Business, Innovation and

Skills (BIS) and the Equality and Human Rights Commission found that 48

per cent of women in Wales suffered negative impacts in work due to having

children (Adams et al., 2016). These experiences with parenthood and work

(the ‘parenthood pay gap’) also show inequalities of outcome, as the

research highlighted that mothers who are not socio-economically deprived

or who have fewer children are less likely to suffer these negative aspects of

motherhood and work.

4.9 A recent report (Welsh Government, 2021c) showed that the disability pay

gap in Wales is 9.9 per cent, which means that disabled people in Wales

earn 9.9 per cent less per hour than non-disabled people. Although this is

lower than the UK as a whole, where the gap is 12.2 per cent, it is still

important to address. A JRF Report from 2018 showed that 39 per cent of

22

disabled people in Wales are in poverty compared to 22 per cent of non-

disabled people, and that this rate is the highest in Wales compared to the

rest of the UK (JRF, 2018). The same report from 2020 discusses how the

coronavirus pandemic will affect poverty levels, exacerbating difficulties in

work, income, and other areas for those who were already struggling (JRF,

2020).

4.10 The Disability Confident Scheme is a UK-wide initiative to encourage

employers to think differently about employing disabled people, bearing in

mind the social model of disability, which aims to remove the barriers in

society and in employment which disabled people with impairments face.

Awareness of neurodiversity (natural variations in brain function, e.g. autism,

dyslexia, or ADHD) is also increasing worldwide. The benefits of having a

neurodiverse workforce are becoming apparent, as employers draw on the

different strengths and talents of their neurodiverse employees to think

differently from others in their team (CIPD, 2018). The Welsh Government,

for example, follows the Disability Confident Scheme as well as

implementing the Social Model of Disability.

4.11 Working conditions and inequalities in work can also contribute to other

inequalities of outcome, such as health (see the Health section for more

information). Insecure work as well as low or uncertain income contributes to

economic and material deprivation, which is a stressful experience and has

negative effects on wellbeing. Insecure or low-paid work can also directly

affect how much people can afford to eat (see the Living Standards section

for more on food insecurity). Low-income workers are more likely to

experience stressful or dangerous working conditions, involving physical or

chemical hazards, long or irregular hours, shift work, or physically

demanding manual labour, impacting both mental and physical health

(Siegrist et al., 2009).

23

Further reading on work and socio-economic disadvantage

Coronavirus and the impact on disabled people

Future Generations Report 2020: A More Equal Wales

JRF Report: Poverty in Wales 2020

Neurodiversity at Work

Paying to be poor: Uncovering the scale and nature of the poverty premium

Pregnancy and maternity discrimination research findings

Welsh Government Annual Employer Equality Report from 2019-20

24

5. Living standards

Background

5.1 Having a safe, warm, and adequate place to live, with access to enough

nutritious food, are key components of a healthy, happy lifestyle. Good

quality housing improves physical, mental and emotional wellbeing, but

people experiencing socio-economic deprivation are more likely to live in

poor-quality homes which are linked to worse future outcomes. Although

research shows that housing conditions in Wales have improved over the

last 10 years (Welsh Government, 2019f), there are still several issues that

disproportionately affect those experiencing social or economic

disadvantage, including homelessness, fuel poverty, unaffordable housing,

and lack of safety and green spaces.

Key inequalities of outcome due to socio-economic disadvantage –

Living Standards.

Living in inadequate housing affects mental and physical health;

People experiencing socio-economic disadvantage are more likely to live in

overcrowded conditions and have higher chance of experiencing

homelessness and rough sleeping;

It is difficult to own a home for some, especially lower-paid workers;

Deprived areas tend to have lower levels of access to green space;

Some households in Wales are still experiencing fuel poverty (where they

do not have adequate heating or hot water);

Socio-economic disadvantage means you are more likely to experience

food insecurity and have less access to a range of affordable healthy foods;

Those from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities are more likely to

live in rented accommodation and;

Rented accommodation generally of poorer quality.

25

Housing accessibility and quality

5.2 Research commissioned by Shelter Cymru, Tai Pawb, and the Chartered

Institute of Housing Cymru shows that demand for housing in Wales is

currently outstripping supply (Hoffman, 2019). Other issues in housing in

Wales include: rough sleeping and homelessness, waiting lists for social

housing, affordability for renters, accessibility for disabled people, lack of

security of tenure, and inadequate housing conditions (Hoffman, 2019).

5.3 Housing costs are one of the biggest factors involved in socio-economic

deprivation in the UK, especially in areas with the highest housing costs (e.g.

London). Notably, measures that look at incomes before taking housing

costs into account often mask poverty, demonstrating the impact that

housing costs have on people’s finances and budgets (Hirsch & Stone,

2020). Rising housing costs, stricter affordability requirements, and high

deposit requirements especially exclude first-time buyers from the market,

leading to what many are terming a ‘housing crisis’ (McMullan et al., 2021).

Rurality can also compound housing supply issues, due to tourism,

agriculture, or residents buying second homes, making it difficult for people

in rural areas to buy housing (FGC, 2020).

5.4 Private and social renters in Wales have one of the highest poverty rates in

the UK

(JRF, 2020). Renting is particularly costly for those on low wages,

young people, or those working part-time (FGC, 2020), showing how

housing interacts with and exacerbates other areas of potential socio-

economic disadvantage, such as work. High private sector rents make

affording a home difficult, because it reduces people’s ability to save;

furthermore, the cost of buying a home has risen faster than wages, making

entering the housing market difficult for many across the UK (McMullan et

al., 2021). Affording a home is more difficult for certain groups, such as

those working reduced hours, low earners, single people, or young people,

and further compounds the cycle of unaffordable renting (Ibid). However,

due to government schemes (e.g. Help to Buy), the proportion of 25- to 34-

year-olds who own their own home has been increasing (Partridge, 2020).

26

5.5 Social housing is generally more energy efficient due to being newer and

because of improvements made to social housing for Welsh Housing Quality

Standard. Wales has older housing stock in comparison to the rest of the UK

and the private rented sector generally also has the oldest housing stock and

a higher proportion of poor-quality housing (Welsh Government, 2019g).

Notably, half of the Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic population in Wales live

in rented properties compared to under a third of the White population

(Clifford, 2020). Deprived areas also tend to have more overcrowding, which

negatively impacts well-being. This is highlighted in figure 5.2.

Figure 5.1: Overcrowding in Wales by deprivation

5.6 Rough sleeping and homelessness are concerns across the UK and Wales

due to social security reforms and reductions in local authority budgets to

tackle homelessness (EHRC, 2018). Homelessness and rough sleeping

exposes people to harsh conditions and is related to poor mental and

physical health as well as drug and alcohol misuse and offending behaviours

(Fitzpatrick et al., 2015). Becoming homeless or being at risk of

homelessness is associated with increased days missing school for children

in these households (Welsh Government, 2021a). Additionally, in the UK,

Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority people are disproportionately affected by

homelessness (Shelter England, 2020).Evidence supporting this in Wales

has also been found (Shelter Cymru, 2013), but requires more up-to-date

27

examination. Evidence also shows that young LGBTQ+ people are

disproportionately represented in the wider homelessness population, with

the predominant risk of homelessness being family breakdown and/or abuse

at home after coming out (Llamau, 2019).

Fuel poverty

5.7 Effective and efficient heating and hot water facilities are key in the provision

of adequate housing. Fuel poverty affects many people in Wales and is

defined by the Welsh Government as spending more than 10 per cent of

your household income on heating your home. Fuel poverty is a complex

problem which is affected by many factors, including household income, the

cost of energy, and the energy efficiency of people’s homes (Welsh

Government, 2020i). Fuel poverty is more likely to impact vulnerable people,

including those in communities or places of interest (e.g. lone parents, older

people, disabled people, or those in rural areas) (Welsh Government, 2010).

5.8 Living in a cold home has significant impacts on physical and mental

wellbeing (Welsh Government, 2010). Effects on health include increased

respiratory illnesses and stress, as well as excess winter deaths. Lack of an

adequately heated room in which to study can impact on educational

achievement and increase absenteeism from school (Welsh Government,

2010). High fuel bills also impact the amount of money available for food,

social activities or other material necessities, interacting with other areas of

social and economic disadvantage. On the macro level, fuel poverty

increases strain on the NHS and has the potential to impact negatively on

the economy due to higher levels of sickness.

Green spaces

5.9 Access to green spaces is directly linked to improved health and wellbeing,

including better mental and physical health and improved mortality (Public

Health England, 2020). However, research shows that those in economically

deprived areas have less available good quality public green space (Schule

et al., 2019). Those living those in deprived areas may live in more

environmentally polluted areas, exacerbating health-related inequalities of

28

outcome. This shows a direct connection to how health, living standards, and

poverty intersect. In fact, evidence shows that the greatest benefits of green

spaces (such as improved heart rate or incidence of type 2 diabetes) are felt

by those living in the most deprived areas (Twohig-Bennett & Jones, 2018).

Furthermore, children in socio-economically disadvantaged circumstances

may also be exposed to more environmental hazards, such as smoking or

air pollution, which may impact the health and development of children

through conception, childhood and into adulthood (WHO, 2021).

5.10 Communities of interest and those with protected characteristics may

disproportionately feel the impacts that derive from a lack of green space, as

infrequent users of green spaces tend to be female, older, those from Black,

Asian and Ethnic Minority communities, disabled people and those in poor

health, people of lower socio-economic status and people living in deprived

areas (Boyd et al., 2018). Research in England found that Black people are

four times as likely as white people to have no outdoor space at home (ONS,

2020).

5.11 In Wales, green spaces are generally accessible with 71 per cent of people

surveyed finding it very easy to walk to local green space and 15 per cent

finding it fairly easy, as well as 84 per cent of people being either very or

fairly satisfied with the quality of the local green space (Welsh Government,

2021e). However, the Green Space Index shows that over 200,000 people in

Wales

14

still do not live within a 10-minute walk of green space (Fields in

Trust, 2020). Notably, households in material deprivation are less likely to

have access to a garden, as are social housing or private rented homes

(Welsh Government, 2021e).

Food insecurity

5.12 Access to food is another area where poverty, health, and living standards

intersect. Food banks and food bank usage are increasing despite the

abundance of food in the UK, according to the South Wales Food Poverty

14

A previous version of this report contained an error indicating that this statistic applied to the UK as opposed

to Wales. This error has now been corrected.

29

Alliance (2019). Food insecurity is not driven by lack of food, but other

factors, including: inability to pay for food due to permanent or temporary low

income; lack of nutritional and cooking knowledge; lack of access to

affordable and healthy food; and lack of cooking facilities or inability to use

them (South Wales Food Poverty Alliance, 2019). This multifaceted picture

of food insecurity shows the complexity of tackling the issue, with support

needing to come from several intersecting areas.

5.13 People on lower incomes have a lower intake of fruits and vegetables and

increased likelihoods of suffering from diet-related diseases and food

insecurity has a negative impact on children’s health, affecting physical and

mental development (see the Health section for more information). Rurality

can impact access to healthy food as there are fewer supermarkets or other

stores selling food, and there is less variety of types of stores, leading to

what are termed ‘food deserts’. In fact, 8 per cent of deprived areas in

England and Wales can be classed as food deserts, i.e. areas where it is

difficult to access a wide range of healthy foods (Social Market Foundation,

2018). This barrier is more difficult to overcome for disabled people and

those without a car. As previously mentioned, being in work does not

preclude experiencing socio-economic deprivation, and the same is true for

food, as one in six people referred to Trussell Trusts food banks are in work

(Alston, 2018). The pandemic has also highlighted inequalities in the UK

food system and the increasing need for government to safeguard the

economy to reduce food insecurity (Power et al., 2020).

Intersectionality

5.14 This section has highlighted throughout the differences that emerge when

looking at the living standards of different groups, as, for example, those

from Black, Asia and Ethnic Minority communities are more likely to live in

rented accommodation which is more likely to be of poor quality. Disabled

people have higher costs of living than others, with research finding that

disabled adults face extra costs of £583 per month (Scope, 2019). One in

five disabled adults face extra costs of over £1000 a month even after

receiving welfare designed to meet these costs. Costs include specialist

30

goods and services (e.g. adaptations to the home), private transport (e.g.

having to use taxis rather than public transport), energy costs (e.g. higher

heating bills to stay warm), and insurance (e.g. being charged more for life

insurance due to a declared condition) (Scope, 2019). It is important to note

that these costs are not caused by being disabled, but by the systemic

inequality in society.

Further reading on living standards and socio-economic disadvantage

Food Poverty in South Wales: A Call to Action

Out on the Streets: LGBTQ+ Youth Homelessness in Wales

Scope: Disability Price Tag

Tackling Fuel Poverty 2021-2035

The right to adequate housing in Wales

31

6. Health

Key inequalities of outcome due to socio-economic disadvantage – Health

Poorer physical health and lower life expectancies in more deprived areas;

More likely to suffer from non-communicable disease in more deprived

areas;

People in areas of higher deprivation more likely to have poorer mental

health, increased risk of suicide, and are less likely to request help for

mental health;

Reduced access to adequate healthcare for certain communities of interest

and in rural areas;

People from Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority communities are more likely

to suffer health inequalities and experience barriers to accessing healthcare

and exercise/sport;

Women more likely to be unpaid carers;

LGBTQ+ people more likely to suffer from psychological distress;

Disabled people face more unmet needs in healthcare.

Background

6.1 Social and economic deprivation has well-established links with health

outcomes (Walsh et al., 2010; Foster et al., 2018). As the Marmot Review,

the largest review of health equity in England, states: “Health is closely

linked to the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age

and inequities in power, money and resources [which are] the social

determinants of health” (Marmot et al., 2020). The Future Generations

Commissioner’s Report (2020) states the importance of recognising the

“wider determinants of health” to encourage governments to take actions to

address these, pledging that in Wales in the future, “the place that people

are born in or where they live will not dictate their standard of living”.

6.2 The World Health Organisation’s Health Equity report defines the wider

determinants of health and the essential conditions to sustain health as:

32

income security and social protection (i.e. ability to afford the necessary

things to thrive), decent living conditions, social and human capital (e.g.

educational outcomes), access to adequate health services, and decent

employment and working conditions. These social determinants for health

can influence health outcomes and lifestyle choices (WHO, 2008). They also

discuss the importance of a person’s wider environment on health, with

neighbourhoods which foster higher levels of social capital creating

opportunities for improved mental health, more-health promoting behaviours,

and greater likelihood of physical activity (WHO, 2016). This highlights the

importance of thinking about health and deprivation in the context of every

other area of this report in relation to socio-economic disadvantage.

Welsh context

6.3 Despite the importance of health and its links to deprivation being

recognised, the Marmot Review (2020) states that health inequalities have

only widened overall over the past decade, and health inequity is evident in

Wales. Adults in the most deprived areas of the country (such as the South

Wales valleys and some North Wales coastal and border towns) have lower

life expectancies (ONS, 2021a; Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation, 2019)

and adults and children in poorer areas have worse health outcomes than

those in the least deprived areas (EHRC, 2018). In fact, adults living in

deprived areas are almost 4 times more likely to die from an avoidable cause

compared to those in the least deprived areas (Welsh Government, 2019f).

Figure 6.1 shows the difference in life expectancy for males and females

living in the most or least deprived areas of Wales (where 1 is those living in

the most deprived quintile and 10 the least deprived) with those living in the

most deprived areas having lower life expectancies, based on data from the

Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation 2019 (ONS, 2021a).

33

Figure 6.1: Life expectancy for males and females in the most deprived and

least deprived areas of Wales

6.4 According to the National Survey for Wales (2020), in 2020 a total of 71 per

cent of adults in Wales reported good or very good general health, with 48

per cent reporting a longstanding illness and 35 per cent reporting a limiting

longstanding illness. These figures are for all adults (16 years old and over)

in Wales. When broken down into deprivation quintiles, fewer adults living in

more deprived areas report good health (Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2: Percentage of adults (aged 16+) reporting good or very good health

by WIMD deprivation quintile. (2016/17 – 2019/20)

34

6.5 National Survey data for Wales shows that adults in the more deprived areas

of Wales tend to eat fewer fruits and vegetables, have higher BMIs, lower

physical activity levels and smoke more(Welsh Government, 2021e).

Similarly, reporting of healthy lifestyle behaviours tends to be lower in

children and young people from more deprived areas. Recent research

shows that in Wales fruit consumption increases with family affluence and

around one in ten young people from less affluent families meet the

recommended daily physical activity guidelines compared to one in five from

more affluent families (Page et al, 2021). Furthermore, adults and children

experiencing socio-economic deprivation are less likely to participate in

sporting activities, as are ethnic minorities and disabled people (Sport

Wales, 2019). These behaviours translate into poorer health outcomes as

unhealthy behaviours are risk factors for non-communicable diseases and

increased morbidity and mortality (Foster et al., 2018; Stringhini et al., 2011).

Deprived areas do however report lower levels of adults reporting they drink

above the weekly guidelines of alcohol compared to those from less

deprived areas (Welsh Government, 2020b). Although life expectancies and

health outcomes are worse for those in deprived areas, there is no current

evidence the gap is increasing (Welsh Government, 2019f).

Mental health

6.6 Mental health is an important issue for future generations and can be linked

to inequalities. In 2015, 26.8 per cent of adults in Wales reported poor

mental health and wellbeing, and mental health problems among children

and young people are on the rise (EHRC, 2018). Mental health is worse in

the most deprived areas of Wales compared to the least deprived areas

(Public Health Wales, 2019). For example, an average of 30.5 per cent of

people in the most deprived decile of areas in Wales have a GP-recorded

mental health condition compared to 19.3 per cent of people in the least

deprived decile (Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation, 2019). Research

shows that deprivation is linked to increased stress, mental health problems,

and suicide (Samaritans, 2017; Skapinakis, 2005). Suicide rates can be two

to three times higher in the most deprived areas compared to the least

35

deprived, showing an association between area-level deprivation and

suicidal behaviour (Samaritans, 2017). Figure 6.4 shows mental well-being

for the years 2016-17 and 2018-19, measured by the Warwick-Edinburgh

Mental Well-being Scale compared to deprivation quintile and highlights the

lower levels of reported mental wellbeing in more deprived areas in Wales.

These scores were collected as part of the National Survey for Wales (Welsh

Government, 2020b). A higher score indicates better mental well-being. A

similar relationship exists in young people in Wales, with reported mental

wellbeing being lower in young people from less affluent families as well as

being more likely to report elevated mental health symptoms and report

feeling lonely (Page et al, 2021)

Figure 6.3: Mental well-being by deprivation quintile in Wales.

6.7 These links between mental health and deprivation are due to a number of

interrelated factors. People who have never worked or who are in long-term

unemployment report poor mental health more often than those in

employment (EHRC, 2018), An increased risk of suicide is linked to job

36

insecurity, unemployment, and debt and stress further contributes to

suicidality, which means that socio-economically disadvantaged individuals

who are experiencing more stress thus have an increased risk of suicidal

behaviour, and are also less likely to seek help for mental health problems

(Samaritans, 2017). Loneliness and social isolation, which can result from

social inequalities or particularly affect those in certain groups (e.g. older

people, LGBTQ+ people, lone parents), can also worsen mental health

outcomes (Owens & Sirois, 2019).

6.8 Research has also shown that LGBTQ+ people may be more likely to suffer

from higher rates of psychological distress (King et al., 2003). The

Transgender Mental Health study (McNeil et al., 2012) found that 66 per cent

of respondents had accessed mental health services and over half (56 per

cent) had been so distressed at some point that they had to seek urgent

support. A total of 53 per cent of respondents had self-harmed at some

point. Levels of satisfaction with health services (both physical and mental

health) were mixed and were worse than in Wales, with negative

experiences being common, such as hurtful language, using the wrong

pronouns, or lacking knowledge about trans-related issues. Many

respondents felt they themselves had to educate health professionals.

6.9 Women are also more likely to report poor mental health in Wales (EHRC,

2018). More women than men are treated for mental health conditions,

which may in part be because they are more likely to disclose a mental

health problem than men.

Intersectionality

6.10 There are many other examples of the intersectionality between health and

factors such as race, socio-economic status, gender, and age. Health

inequities due to socio-economic status begin from a young age, and thus

children in disadvantaged communities are more likely to experience ill

health which affects their childhood development and educational outcomes

(Hirsch, 2007). Living in a household with a disabled person makes relative

income poverty more likely and material deprivation is twice as likely for

37

disabled people or those with limiting long-term illnesses, compared to those

who are not disabled (Welsh Government, 2019f). Disabled people across

the UK are also more likely to struggle to access healthcare and have more

unmet needs in healthcare due to waiting lists or costs (Sakellariou &

Rotarou, 2017). Figure 6.4 demonstrates how more deprived areas have

higher numbers of people reporting an impairment.

Figure 6.4: Disabled status by area deprivation

6.11 Physical and mental health are affected by housing or employment, as

problems in these areas can increase stress, and lower income jobs are

more likely to be hazardous (EHRC, 2018). Housing and living conditions are

linked directly with increased risks of accidents, spread of disease and

physical effects of overcrowding as well as indirectly through effects on

relationships, feelings of security, social stations and a sense of inclusion

(Hagell et al, 2018). Housing tenure is also important with insecure housing

and homelessness impacting adversely on educational and employment

outcomes, higher levels of substance misuse and an increased likelihood of

38

nutritional and infectious diseases (ibid). Access to green spaces can

improve wellbeing and health, but rurality can worsen outcomes if people

cannot easily access healthcare. More cohesive communities can reduce

social isolation and loneliness, improving health as people build stronger

relationships and more ‘social capital’ (Healthy People, 2020). Deprived

areas are more likely to be ‘food deserts’, with fewer supermarkets and less

access to healthy foods, leading to more food poverty and reliance on food

banks or unhealthy foods, increasing rates of diet-related diseases

15

(The

Social Market Foundation, 2018).

6.12 The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted underlying inequalities of outcome

in healthcare and has exposed vulnerabilities in the healthcare system

(Public Health Wales, 2021). Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic populations

have been disproportionately affected by COVID both directly and indirectly

(Razai et al., 2021). These inequalities have always been present in

healthcare systems in the UK (Byrne et al., 2020), but the coronavirus

pandemic particularly shed light on these structural inequalities and led to

the establishment of the Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic COVID-19 Socio-

economic Sub Group which carried out a full report on the situation in Wales

in 2020. They found that the Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic population in

Wales has been disproportionately affected both through unequal health

outcomes and structural inequalities by COVID-19 even after adjusting for

region, population density, and socio-demographic and household

characteristics (Clifford, 2020).

6.13 Furthermore, data for England from the Office for National Statistics (2021b)

showed that 59.5 per cent of people who died with coronavirus in England

were disabled (defined as self-reported disability through the 2011 Census).

This disparity still arose when looking at age-standardised data. They

conclude by stating that no single factor explains the considerably raised risk

of death from coronavirus among disabled people, and the factors include

socio-economic and geographical circumstances as well as pre-existing

health conditions. Disabled people in Wales have also been affected by

15

See Living standards for more information on food deserts and food banks.

39

structural inequalities. They have disproportionately fallen behind with

household bills during the pandemic, with disadvantaged positons in the

labour market, poorer quality housing and increased costs associated with

being disabled contributing to unequal outcomes (Welsh Government,

2021i).

6.14 Covid-19 also highlighted structural health inequalities among children and

young people in Wales. Children in households without access to outside or

indoor space where they can exercise can be vulnerable in the short term to

poor mental health and have the potential to form poor exercise habits, and

reductions in physical activity were greatest among children from poorer

socioeconomic backgrounds (Sport Wales, 2020). School closures and

income reductions also increased food insecurity, with demand for foodbank

services increasing (Trussel Trust, 2020)

6.15 However, it is important to note that more research needs to be carried out

to fully establish why there are disparities in health outcomes for different

groups, as these disparities most likely arise from a complex combination of

genetic, biological, and social causes. The first Welsh Health Equity Status

Report initiative, focused on a sustainable response to COVID-19 in Wales,

provides further details on the key population groups that have been most

affected by the pandemic and highlights that the pandemic provides an

opportunity for transformative recovery to ensure the wellbeing of current

and future generations (Public Health Wales, 2021).

Accessibility to healthcare and wellbeing facilities

6.16

Access to appropriate health- and wellness-related facilities (such as GP

surgeries, gyms or leisure centres) is a key issue when considering health-

related inequalities of outcome. Particular groups struggle to access

healthcare of the same consistency and quality as those who experience

less socio-economic disadvantage. These groups include homeless people,

people with learning difficulties, migrants/refugees, prisoners, Black, Asian

and Minority Ethnic Populations, transgender people, and those living in rural

areas (EHRC, 2018).

40

6.17 Research shows that residents in the most deprived areas of Wales have

lower levels of physical activity (Welsh Government, 2020c). This could be

due in part to the accessibility of sports facilities (although the cost of gyms

is not necessarily higher) (Evans et al., 2013), as poorer areas are less likely

to have adequate leisure, gym or sports facilities, especially in more rural

areas (Higgs et al., 2015).

6.18 Another barrier to accessing sports and other facilities related to health is

racism. Racism was highlighted by Sports Wales (2019) as a factor that

makes people less likely to participate in sports, along with lack of facilities,

social isolation, and cultural expectations. The interactions between sport

and race, social justice, social class, and gender are complex and research

has highlighted the need for acknowledgment of intersectionality in this area

when enacting policies (Dagkas, 2019). This reflects the wider need to

consider health and its interactions with all protected characteristics and

aspects of socio-economic inequality when thinking about health and health

outcomes.

Unpaid caring

6.19 Unpaid caring responsibilities impact the physical and mental health of both

the carers and the ones being cared for. Several factors are associated with

caring for someone for more than 5 hours a week, including: being female,

being aged 45 and over, living in social housing, living in one of the 20 per

cent most deprived areas of Wales, feeling low levels of life satisfaction,

having a limiting long-term illness, and being unemployed (Welsh

Government, 2021b). Informal caring responsibilities largely fall on women

until late in life when men form a larger proportion of informal carers

(Dahlberg et al., 2007).

6.20 Being an informal, unpaid caregiver leads to inequalities of outcomes, as

carers cannot devote as much time to their own wellbeing or development,

they may suffer from their own physical or mental health problems, and they

may experience loss of earnings or impact on work (Carers UK, 2019; Welsh

Government, 2021b, 2021h). However, these outcomes are not always

41

straightforward and some research suggests caregivers may have increased

physical or mental wellbeing (Brown & Brown, 2014). Carers can be

considered ‘hidden patients’ as they may struggle but not be offered

appropriate support and this can particularly affect those from Black, Asian

and Ethnic Minority groups, who may experience inequity in service

provision and may face barriers such as language or lack of cultural

understanding from service providers (Merrell et al., 2006).

Further reading on health and socio-economic disadvantage

Adult general health and illness (National Survey for Wales): April 2019 to

March 2020

Adult lifestyle (National Survey for Wales): April 2019 to March 2020

Dying from Inequality: Socio-economic disadvantage and suicidal behaviour

Future Generations Report 2020: A Healthier Wales

Trans Mental Health Study 2012

Welsh Health Equity Status Report initiative (WHESRi): Placing health equity

at the heart of the COVID-19 sustainable response and recovery: Building

prosperous lives for all in Wales

Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) 2019: Results report

Public Health Wales 2018: Health and its determinants in Wales

School Health Research Network, National Report, 2019/20

42

7. Justice

Background

7.1 The right to feel safe and protected by the law is paramount in all modern

democratic societies. Everyone has a right to feel safe in their community

and people interacting with the justice system have the right to be treated

fairly. However, socio-economic deprivation is linked to greater chances of

interacting with the justice system, being a victim of a crime, or not feeling

safe in a community.

7.2 In Wales, many areas related to crime are not devolved, such as policing,

criminal justice, and media and internet regulation. Therefore, as justice is

controlled by the UK Government, there is no integrated approach to the

justice system and “the impact of [budget cuts] on Wales has been

significant” (Commission on Justice in Wales, 2019:8). The Welsh

Government has responsibility for contributing to safety and cohesion of its